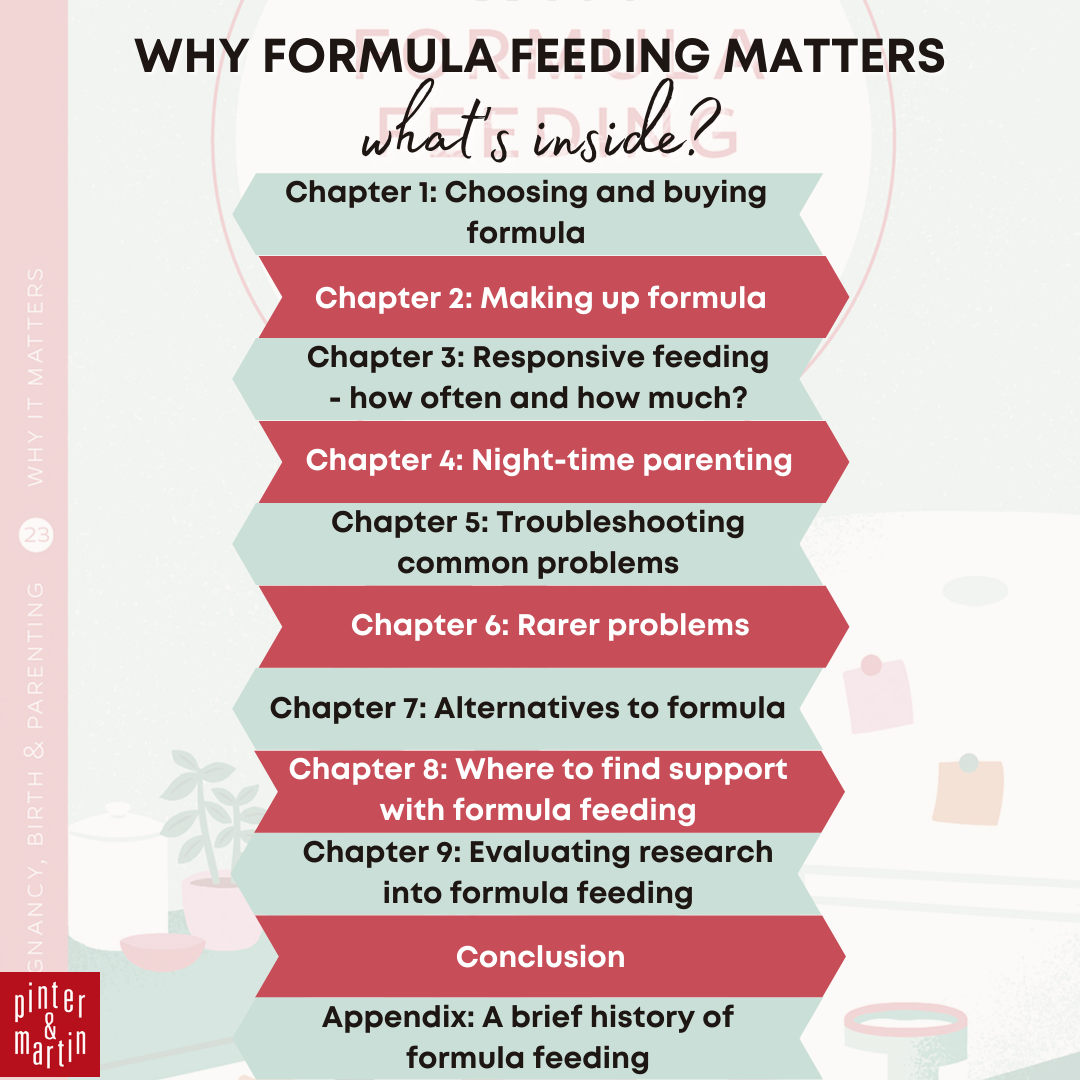

This article has been taken from chapter 3 of “Why Formula Feeding Matters” by Shel Banks, published by Pinter and Martin in 2022. Click here to buy a signed copy of the book, or here to watch a podcast about it.

How do we know when our babies are hungry?

Some of the common early feeding cues which babies exhibit from birth include:

- licking lips and making ‘lip smacking’ noises

- opening and closing mouth

- sucking on lips, tongue, hands, fingers, toes, toys, clothing, or almost anything else

If these early ‘cues’ are rewarded with fairly immediate feeding then a baby will be happy and satiated, and they will continue to use the cues to communicate with their carers. If the feeding cues are never responded to, then the baby will soon stop wasting energy on producing them: sadly, this is part of how babies can be ‘trained’ to go longer between feeds, and never ask for feeds before they are offered them.

Active feeding cues might include:

- rooting around on the chest of whoever is carrying them

- fidgeting or squirming around a lot

- displaying discomfort or grunting

- trying to position for feeding, either by lying back or pulling on your clothes

- hitting you on the arm or chest repeatedly

- fussing or breathing fast

Later feeding cues will include:

- Moving head frantically from side to side

- Starting to cry

Why crying is not a feeding cue

It is important to note here that crying is not really a feeding cue: crying is a sign that we have failed to pick up on the earlier feeding cues, and the baby is now very unhappy, hoping to get us to notice them and realise we have missed their cues. Eventually, even a very hungry baby will cease crying to attract our attention and effectively ‘shut down’ to conserve energy. Sometimes parents and carers take this as a sign that the baby must have been tired and not hungry after all, particularly if the baby is being put into a routine for feeding, and this wasn’t an allocated time for feeding. But when that infant does wake up, they will not act like a happy well-rested little person, but instead like a cranky ‘hangry’ baby, who shrieks and seems very high-maintenance, because they went to sleep hungry and now they are really hungry, with no time to wait for us to figure out their feeding cues.

Some words about crying babies

‘A baby’s cry is precisely as serious as it sounds.’ Jean Liedloff, The Continuum Concept: In Search Of Happiness Lost

As mentioned above, some of the instincts babies are born with are ‘use it or lose it’ – a baby whose feeding cues are never rewarded with feeding, who is always left to cry, will soon stop exhibiting the feeding cues as they just use up valuable energy. If they find that they have to cry to be fed, then they will always do that. These babies may be seen as very high maintenance. However, if even their cries do not result in food, they will soon learn not to use up energy crying. They have learned that no one will respond. These babies often stop showing any emotions which are not rewarded with anything good, such as at sleep times if the parents are trying to ‘sleep train’, but sometimes babies of parents who have trouble with their own emotions can just start to suppress their emotions generally and have unrestrained outbursts now and again.

A happy baby is one whose needs are recognised and met as soon as possible, and who is held and comforted when they are unhappy.

Overfeeding

You may have heard health professionals say that ‘you cannot overfeed a breastfed baby’. This is because breastfed babies do not usually take more milk than they need, for three reasons.

Firstly, breastmilk changes during a feed from more carbohydrate-dense watery milk at the start, to denser, fattier milk towards the end.

Secondly, a hormone in breastmilk called leptin makes the baby feel fuller as the feed progresses.

Thirdly, the mother’s milk ejection reflex responds differently at the start of the feed when the baby suckles quickly and rhythmically, than to the far slower suckles with long pauses that come later in the feed, when the baby may seem not to be feeding at all, and can seem like they are sleeping.

All of these things mean that a breastfed baby slowly realises they’re getting full, much as we adults do when eating a meal with breaks between the courses, or at a buffet where we have to keep getting up from our seat and going back to the table to get more.

When bottle-feeding, whether there is breastmilk or formula in the bottle, things are different. The baby will – because of their instinct to suck if something touches their palate, and swallow if liquid is at the back of their mouth – keep going until they have finished the bottle, if they are allowed to, and especially if they are encouraged to, to prevent wastage or to try to make the gap until the next feed as long as possible.

What we can offer babies to counteract this tendency, based on new best-practice guidance, is ‘paced feeding’ or ‘responsive bottle feeding’: this allows the baby more control over their feeding and encourages them to feed more slowly, taking breaks during the active parts of the feed rather than downing the bottle in double-quick time. For full descriptions of the method, see the article by Emma Pickett IBCLC on responsive bottle feeding, page 18 of the 2018 Department of Health/Start4Life Guide to Bottle Feeding, and the first side of a leaflet called ‘Infant milk and responsive feeding’ published by Unicef Baby Friendly and First Steps Nutrition Trust.

In brief, it’s about allowing the baby to be in control and responding to their needs by feeding when they have given cues, keeping baby more upright than the traditional ‘flat on back’ position, allowing the baby to choose to take the offered teat, and with the bottle held as a more shallow angle so that gravity is not pushing milk into the baby’s mouth. Then the adult would watch the child for signs that they need a break and pause the feed, perhaps actually lifting them upright to get any trapped gas out.

How much milk?

Many parents wonder how much milk they should offer at each feed, and how they will know when their baby has had enough milk in a day or a week. Should they follow the instructions on the packaging to judge what their baby will need? As you can see from the table below, particularly the columns in bold (which have been added especially for this book, to show the actual volume the company anticipates a baby might require in 24 hours), it’s not straightforward. It’s often quite confusing!

| Approx age | Approx weight | Number of level scoops | Quantity of water (ml) | Quantity of water (fl oz) | Feeds in 24 hours | Total feed volume (ml) | Total feed volume (fl oz) |

| Birth | 3.5kg/7lb 5oz | 3 | 90 | 3 | 6 | 540 | 18 |

| 2 weeks | 4kg/8lb 8oz | 4 | 120 | 4 | 6 | 720 | 24 |

| 2 months | 5kg/11lb | 6 | 180 | 6 | 6 | 1080 | 36 |

| 4 months | 6.5kg/14lb 5oz | 7 | 210 | 7 | 5 | 1050 | 35 |

| 6 months | 7.5kg/16lb 5oz | 8 | 240 | 8 | 4 | 960 | 32 |

| 7–12 mths | – | 7 | 210 | 7 | 3 | 630 | 21 |

Typical ‘Feeding Guide 0–12 months’, adapted from formula milk packaging in UK, 2019

Looking at this table, is your three-day-old baby going to be able to take 540ml/18fl oz in one day – especially via six 90ml meals? Of course not. As we have established, babies’ tummies are tiny and of course they are in proportion to their bodies: a rough guide is that everyone naturally has a stomach the size of the palm of their hand. Look at your baby’s hand. New babies’ stomachs do grow quite quickly – look online for pictures of ‘infant stomach capacity’ and you’ll find pictures likening stomach sizes at different ages in the first days and weeks of a newborn baby’s life to various fruit and nuts and so on, to give you an idea. Some healthcare professionals use so-called ‘belly balls’ to illustrate this too, but of course they can’t be completely accurate as babies vary in size and build just as adults do.

Going back to the table, perhaps your baby is now 13 days old. Are they currently taking only six feeds a day, totalling 540ml in total? Well, gear up folks, because according to the packaging, tomorrow those same six feeds need to cram in 720ml as your baby hits the two-week milestone! And how many 13-week-old babies would be happy to go four hours between each feed? Clearly it’s not possible, and nor is it desirable. The manufacturers themselves say these charts are a guide.

As you can see in the table from the two columns which are in bold type, the suggested volume of feeds in 24 hours actually drops to 1,050ml at 4–6 months, from 1,080ml at 2–4 months. Do babies actually need less milk as they get older? It seems counter-intuitive and it’s just not the experience of families: babies at this age seem to be less satisfied and want more, and parents start to worry their babies are not getting enough from milk alone, and may need solid foods – of course, the recommendation is that food other than milk is introduced from 26 weeks, and following signs of developmental readiness.

– – – – – –

This article has been taken from chapter 3 of “Why Formula Feeding Matters” by Shel Banks, published by Pinter and Martin in 2022. Click here to buy a signed copy of the book, or here to watch a podcast about it.